- Home

- Ambi Parameswaran

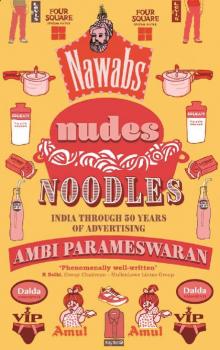

Nawabs, Nudes, Noodles

Nawabs, Nudes, Noodles Read online

NAWABS, NUDES, NOODLES

India through 50 Years of Advertising

Ambi Parameswaran

MACMILLAN

This book is dedicated to the unsung heroes of all great advertising – The Clients

Contents

Introduction

Section One: People

The [In] Complete Man

I am a Complan Girl! I am a Complan Boy!

The Tingling Freshness of Teens

Jo Biwi Se Kare Pyaar…

Ab Main Bilkul Boodha Hoon, Goli Kha Ke Jeeta Hoon!

Twacha Se Meri Umar Ka Pata Hi Nahi Chalta

Section Two: Products

Only Vimal

Bachche Toh Bachche, Baap Re Baap!

Hamara Bajaj, Hamara Bajaj

Ghar Ghar Ki Raunaq Badhani Ho

Jai Jawan! Jai Kisan!

Har Ek Friend Zaroori Hota Hai

Section Three: Services

Baraatiyon Ka Swagat

Tan Ki Shakti, Man Ki Shakti

Zindagi Ke Saath Bhi, Zindagi Ke Baad Bhi!

God’s Own Country

Naukri: H for Hitler, A for Arrogant

Kyaa Haal Bana Rakha Hai!

Asli Swad Hai Cricket Ka

Section Four: Ad Narratives

Doodh Doodh Doodh, Wonderful Doodh

Meri Khubsurti Ka Raaz

Bole Mere Lips, I Love Uncle Chipps

No Squeeze, No Wheeze, No Navel Please!

Last Word

Acknowledgements

Notes

Suggested Reading

Index

Introduction

Divining Societal Trends Using Advertising

I WAS LOOKING for my favourite blue jacket and could not find it in my closet. I was sure that the jacket was not with the dry-cleaners. Then I remembered that the previous week I had flown to Bangalore, and the flight back was terribly delayed. It had landed well past midnight. I realized that I had forgotten my jacket in the aircraft. Several phone calls later I was at the Lost and Found counter of Indian Airlines – this was in 1993; those were the days when you did not have to scratch your head about which airline to book. It took them just a few minutes to locate my jacket since I had the exact details of the flight. The person manning the department mentioned that they get on an average ten spectacles and sunglasses every few days, and enough books to open a library every few years. A dress blazer was an odditiy in the store room. I explained that I work in advertising, the client meeting had been rough and the flight was late. The executive mockingly said, ‘It took you five days to figure this out? Oh, you must have been drunk; you guys in advertising drink a lot, don’t you?’ This was a full decade or more before Mad Men aired on American television and damaged the already bruised image of admen. The comment riled me up. I sat the old man down and gave him a lecture on what we do in the advertising business. He was not expecting that, but took the lecture in good spirit. Finally, we parted as friends, me with my jacket, him with a slightly better understanding of the ad business.

While everyone is happy to speak about an ad they saw on television, their knowledge about the industry is scant. Advertising agencies have existed in the country for well over 100 years now. However, it was only in the last fifty years, or more specifically since the winds of liberalization started blowing strongly from 1991, that advertising as an industry has come into its own – truly reflecting the changing Indian consumers, their aspirations and desires.

From a societal point of view, roles played by man, woman, father, mother, grandparents, even the importance of rituals, festivals and money have changed. The rapidly diminishing effect of the deep divisions of class and caste as prescribed by the Manusmriti is evident in consumer India, at least in the urban markets.

Popular films, television programmes, novels, magazines and now digital media have been interesting reflections of societal changes. Be it the righteousness of the epic Indian mother (Mother India), the aggression of the angry young man (Zanjeer), to the lover boy phase (Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge) and to the NRI with a heart (Swades) phase, films have reflected the changing ethos of Indian society. In a similar vein, television programmes have also evolved from the days of partition drama to joint-family business sagas to saas-bahu serials to depicting IAS women on prime-time television; and as can be expected, religious mythologies continue to find their pride of place in Indian television. Several books have captured the changing chiaroscuro of Indian movies and television.

Advertising too has become a significant window to studying the transformation of Indian society, its desires and its needs. In a conventional sense, advertising has often attempted to change behaviour by introducing new products and selling them on the basis of rational and emotional benefits. At times, advertising has used social trends to sell products and services under the radar.

Often advertising has tried to stay a few steps ahead of society, thereby signalling a future trend. Sometimes it has looked at the past to hark back on an age-old ritual, custom or lifestyle to make the right connection. At a rudimentary level, advertising played a role in helping Indians discover new products and services. From the days when Dalda was demonstrated at grocery shops to the way Indians were weaned away from coal to a tooth powder to a tooth brush – ironically, today we are offered carbon-infused toothbrushes – advertising has tried to sell products rationally. Often adding a touch of emotionality as well.

While American cultural historian Jackson Lears dismisses advertising as ‘the folklore of industrial society’, I believe Indian advertising, considering the last five decades, provides not just folklore but also some interesting insights into a society in transition.1

Roland Barthes, the French philosopher, linguist and semiotician, observes that commercials for products like laundry detergent or margarine work only because they tap into ideas consumers already have. These ideas have been elevated into myths. So, while the Greeks had Homer, we have professional wrestling and Hollywood, he says. If I may add to that, we also have television commercials which in their own form have become part of urban myths.

Advertising has tried to reflect the changes in the roles of men and women since the day a pressure cooker was sold as a symbol of love to the present day when a mobile service brand offers itself as a bridge between a woman boss and her subordinate husband.

The importance of children is not to be underplayed in a country that is one of the youngest in the world. Advertising in India seems to suffer from an overdose of children who are used to sell products ranging from noodles to soap, detergents to mobile phones, even cars are within their aspirational reach.

The depiction of women has also changed dramatically from the days of the coy bride being led into the house, to the ‘Mummy’ who can spin magic to solve a problem to a dark-skinned woman going through the wedding ritual with her daughter eager to join her in the saat pheras round the fire. No other single consumer group has been depicted in such a diverse fashion.

If women have become more and more confident, men are being depicted as increasingly caring and thoughtful – even if it is wishful thinking on the part of copywriters, but there are a growing number of talented women vying for top posts in ad agencies. The days of macho men having a bath in the open with a red carbolic soap has given way to a man who helps his wife with the cooking. Not that macho men are missing. Often they are shown to be relying on the power of a deodorant or a snazzy undergarment to snag the luscious bhabi.

Young adults as a group too have evolved to a new level. From the days of carefree fun, today they expound new philosophies on corruption, freedom of speech and suchlike. Gender difference is getting bridged as women get their own two wheels and ask, ‘Wh

y should boys have all the fun?’

Getting a job used to be the ultimate achievement. Advertisements depicted men wearing smart formals washed with the best detergent landing the best job, and celebrating the achievement by rushing home and lifting up the devoted wife. No longer is getting any job enough. Now ads show subordinates demanding more from their bosses and even insulting them by calling them names like ‘Hitler, arrogant, rascal…’ when they are being unreasonably difficult.

Looking young and fair continues to be an obsession with Indian consumers and marketers. In addition there is this whole new mania about smelling good. While fairness cream advertising was once restricted by Doordarshan into describing gori as nikhri – the dictionary meaning of nikhri is improved or better, but Hindustan Unilever has been using it so consistently to promote its fairness cream that today nikhri almost means fairer to the lay public – all those taboos fell by the wayside with the opening up of television. Today, fairness obsession has even captured the menfolk. In middle-class homes, there are as many men’s cosmetic products as there are women’s cosmetic products, all spurred by advertising and the social pressure to look good.

When mobiles came into the country they were prohibitively expensive. One could not have even imagined that in less than ten years, it would be in the hands of every fruit vendor on the street. Advertising, and of course pricing, played a major role in the growth of mobile phones. From the days of pre-paid to free incoming calls to per-second billing, mobile marketers innovated and have not been shy of crying from the rooftops to grab the attention of the consumers.

Almost in a playback of the mobile revolution, e-commerce merchants are using high-power discount messaging to break consumer intertia in an almost perverse way. They are now driving consumers to shop from their sofasets. This battle to change consumer behaviour is being fought in the 2010s and the results will be visible in just a decade or less.

Advertising has had its share of controversies. At one time, sanitary napkin ads surprisingly were restricted to the post 10 p.m. slot on Doordarshan, though condom ads were aired at all times. When Tuffs shoes commissioned an ad that showed Milind Soman and Madhu Sapre in the nude, it led to a court case for obscenity that went on for over two decades. Fastrack, a watch brand owned by the Tatas, decided to fly a flag for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) community by asking people to come out of the closet and embrace their sexuality. Since the days of Doordarshan, which even restricted the display of the navel of a model in a sweetener ad, we have truly come a long way.

Nawabs and other royalty too have modelled for premium suiting brands and now the new nawabs of India, its film stars and cricket stars, are endorsing apparel brands. If sarees have started vanishing from ads, we are seeing the birth of new kinds of apparel for both men and women, call them kurtis or Modi kurtas, we are bombarded with an increasing range of apparel choices.

A frame-by-frame content analysis of consumer product television advertising in India, released over the last fifty years, shows some very interesting facts. For instance, the way women are presented has changed dramatically. The number of words used in each advertisement has increased. Even products like soap have a wordy explanation.

Advertisers have at times used social consciousness as a tool to further the aims of commerce. Amul’s ads celebrated the milk co-operative movement, Tata Steel proudly said, ‘We also make steel’ and Tata Tea issued a clarion call to counter corruption through its ‘Jaago Re’ campaign.

Why is this book relevant today, more than ever? The last ten years have seen an explosion of consumer choice and media consumption. Print is under attack from digital, even though Indian language print is still vibrant and blooming. Television has been growing rapidly as well and the numbers are astounding. There were a grand total of fifty-five licensed television sets when Nehru died in 1964, about a hundred thousand when Indira Gandhi declared emergency in 1975, a little over two million when the Asian Games came to Delhi in 1982, thirty-four million families owned a TV set when Manmohan Singh opened up the economy in 1991 and when Narendra Modi was sworn in as Prime Minister in 2014, over 60 per cent of the 250 million homes in India had a television set.2 But televison has now geared up to combat digital invasion, with consumers ready to watch television content on their mobile screens. Multiplex movie screens have opened a parallel distribution for non-mainstream films. The future holds many more surprises as was evidenced a few years ago with the monster viral hit Tamil song, ‘Why this kolaveri di?’

The book is organized into stand-alone chapters with each chapter looking at the changes in society and advertising through a different lens. Each chapter may ask a few questions and present some reasons behind what is happening around us and how advertising is shaping and getting shaped by it.

The objective of this book is to provide a window to the changing Indian consumer landscape for students of management, marketing, advertising, sociology and media studies. It also hopes to make for interesting reading for the millions of consumers out there who watch and comment on advertisements. It will probably leave all its readers with some questions to answer: Where is our society headed and how can marketing play a more meaningful role in creating positive social change? And, hopefully, the next time an adman seeks to locate his forgotten dark blue blazer, the person on the other side will be a little more sympathetic and a little more aware of the troubles and travails of the Indian advertising business!

SECTION ONE

PEOPLE

The [In] Complete Man

BEHIND THE ERSTWHILE Moore Market in Chennai was the Corporation Stadium where I spent many an evening witnessing sports of all sorts. From the National Hockey Championships to the Ranji Trophy cricket matches, it was a part of my routine during my school days in the early ’60s. The fact that my Dad’s business was close by and that I loved to spend hours wandering around the bookshops at Moore Market were added advantages.

One of the most exciting things I had the opportunity of watching was the rekla race. While these still exist in some form in rural Tamil Nadu, they are no longer popular in the metropolitan city of Chennai. In these races, two men stood in a little chariot that was pulled by two bulls and raced around the stadium to the hooting of enthusiastic crowds. For those of you who may have seen the Hollywood movie Ben Hur and its chariot race, the rekla race was the Chennai equivalent. The bulls were semi-trained and the men riding the chariots were highly trained, but the races invariably ended in collisions, broken bones and more. The rekla race and jallikattu are very popular in rural Tamil Nadu. Jallikattu is another form of bull running where young men try to chase and catch an untrained bull and bring it to its knees. In a strange way, Indian men seemed to have a great fascination with the bull, from the seals of Mohenjo-Daro to the full-page obituary put out by a farmer on the demise of his favorite bull in the Karimnagar edition of the Telugu daily Eenadu.1

As a reflection of the ethos of those times, advertisments aimed at men had an overt macho personality. Brands like Lifebuoy showed brawny men playing football in mucky, rainy conditions only to get into a shower and bathe with the carbolic soap Lifebuoy to the tune of ‘Tandurusti ki raksha karta hai Lifebuoy, Lifebuoy hai jahan, Tandurusti hai wahan’ (Health is protected by Lifebuoy. Where there is Lifebuoy, there is health). Lifebuoy ran a series of ads featuring men engaged in sports such as football set in a rather semi-urban environment. The Lifebuoy tag line from Lintas, the Lever ad agency, ‘Where there is Lifebuoy, there is health’ was the first ad slogan that was equally popular in urban and rural India.

Colgate toothpower in the ’80s took a different angle at the brawn vs brain issue, again aimed at both urban and rural consumers. The film is set in an akhara where muscle-bound wrestlers do their daily practice bouts. A burly young man has just finished his routine and picks up a piece of sugar cane and bites into it. But his dental cavities make him cry with pain. His young sister walks up and gently chides him, ‘Badan ke liye doodh aur ba

dam, lekin daantho ke liye koyla? Bhaiya, kabhi kabhi deemag ki bhi kasrat karni chaiye’ (For your body you consume milk and almonds but you clean your teeth with coal dust? Brother, at times you should also exercise your brains, not just your body). The ad crafted by Kamlesh Pandey at Rediffusion then presented the advantages of Colgate toothpowder. Here was a brand that decided to use the Indian man’s fascination with bodybuilding to its advantage by presenting its toothpowder in an interesting context.

The ’70s and ’80s also saw cigarette advertising enter the cinema halls of India, when bad songs in movies often drove viewers out for a smoke break. While Charminar cigarette said ‘Relax! have a Charminar’, Scissors said, ‘Men of Action-Satisfaction. Scissors always satisfies’. Four Square launched as India’s first king-sized cigarette in the late ’70s offered the dream to ‘Live Life Kingsize’.

When Godfrey Philips wanted a campaign for their Red & White cigarette – and I was part of the team that worked on the campaign – the agency decided to position the brand for men who did good deeds, but did not hanker after the accolades that follow. The campaign ‘Hum Red & White peene walon ki baat hi kuch aur hai’ (those who smoke Red & White are a different breed) went on to run for more than a decade. The model chosen to play the hero in the Red & White films, Raj Babbar, went on to become a very popular film star and has successfully moved into politics as well. A similar fate awaited the Charminar model, Jackie Shroff, without the political afterlife.

While brands aimed at the lower socio-economic groups were speaking of brute strength and power, in the 1980s we started seeing brands trying to appeal to the new affluent in more sophisticated ways.

Cherry Blossom shoe polish ran a very popular campaign that said ‘Something special is coming your way – Did you Cherry Blossom your shoe today?’ The ad showed the beautiful face of the biggest supermodel of that era, Nandini Sen. The Hindi version of that line was also a classic, ‘Chalte chalte kismat chamke’ (Your luck will shine as you walk).

Nawabs, Nudes, Noodles

Nawabs, Nudes, Noodles